V. Black and White in Wuthering Heights

Rosalind Whitman

-

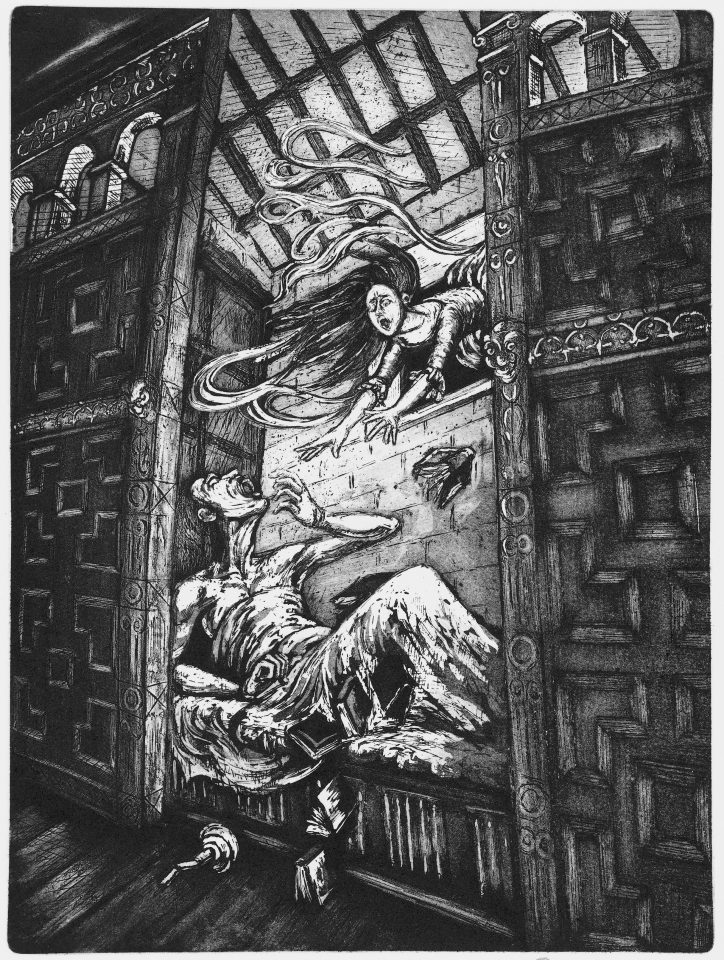

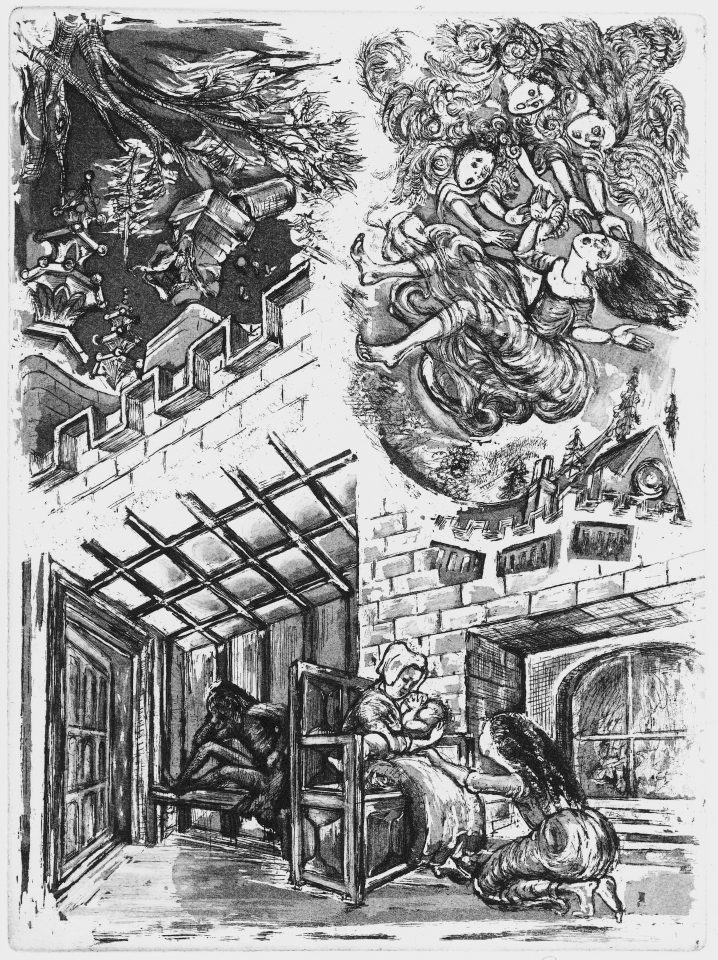

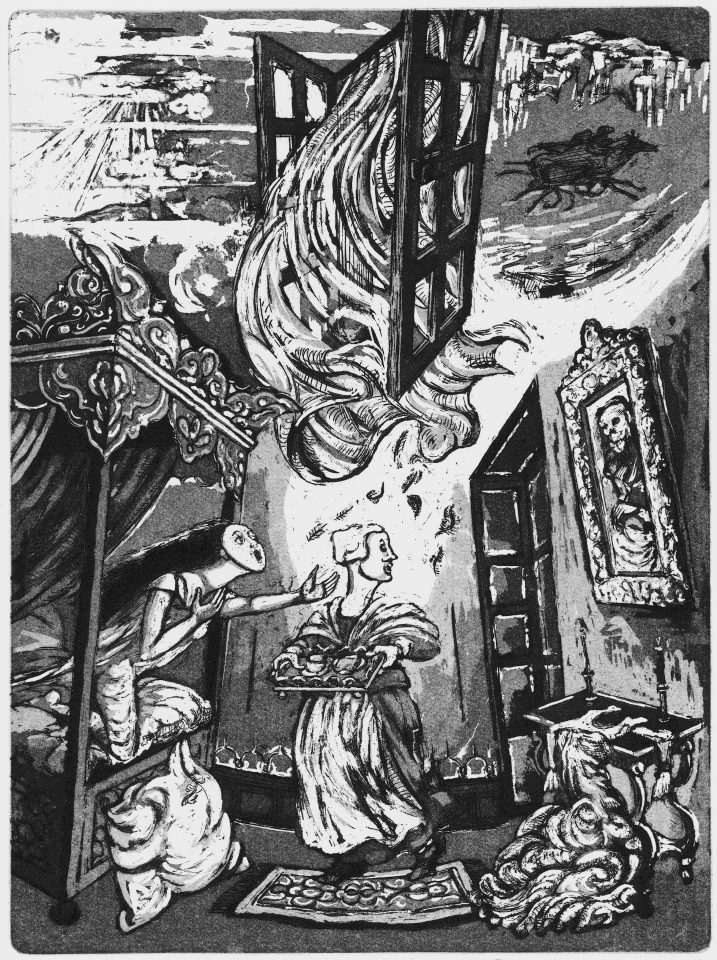

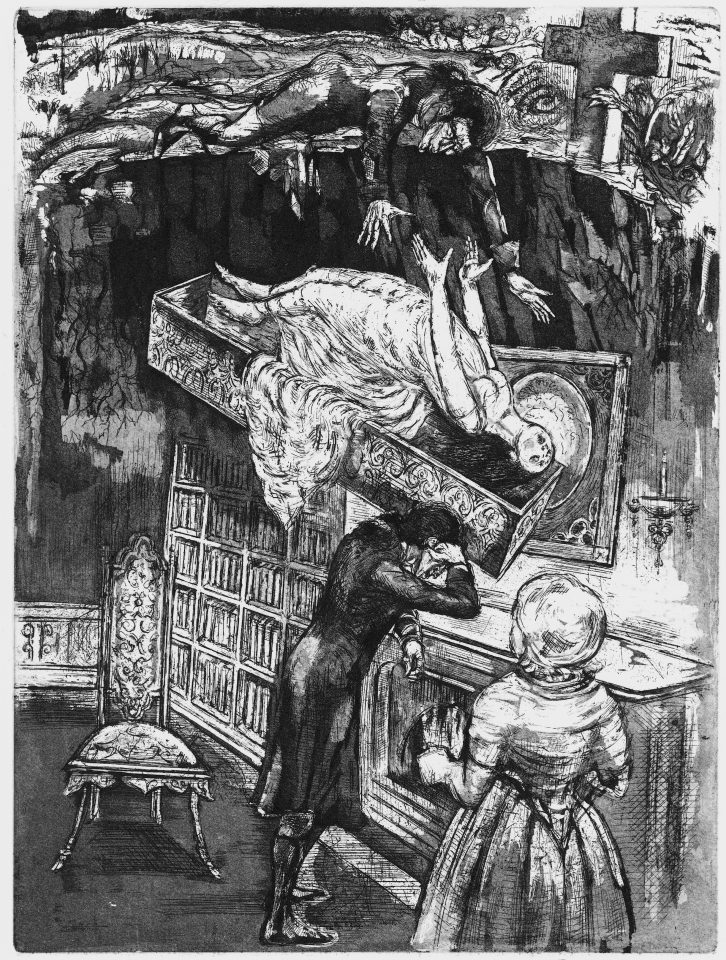

Lockwood's Dream, etching

-

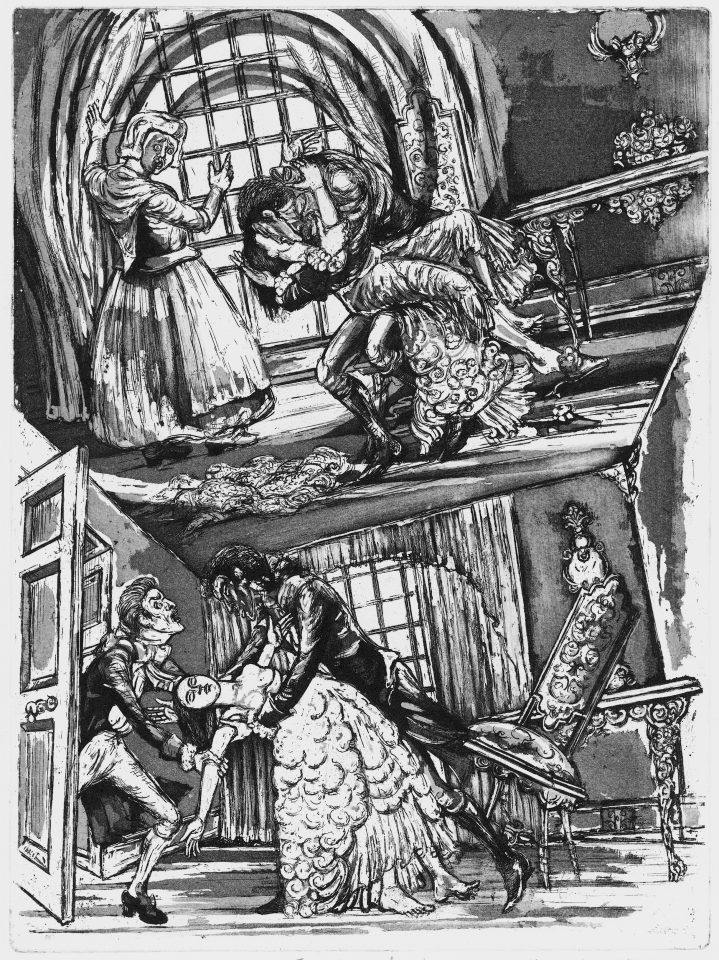

Lockwood Attacked by Dogs, etching

-

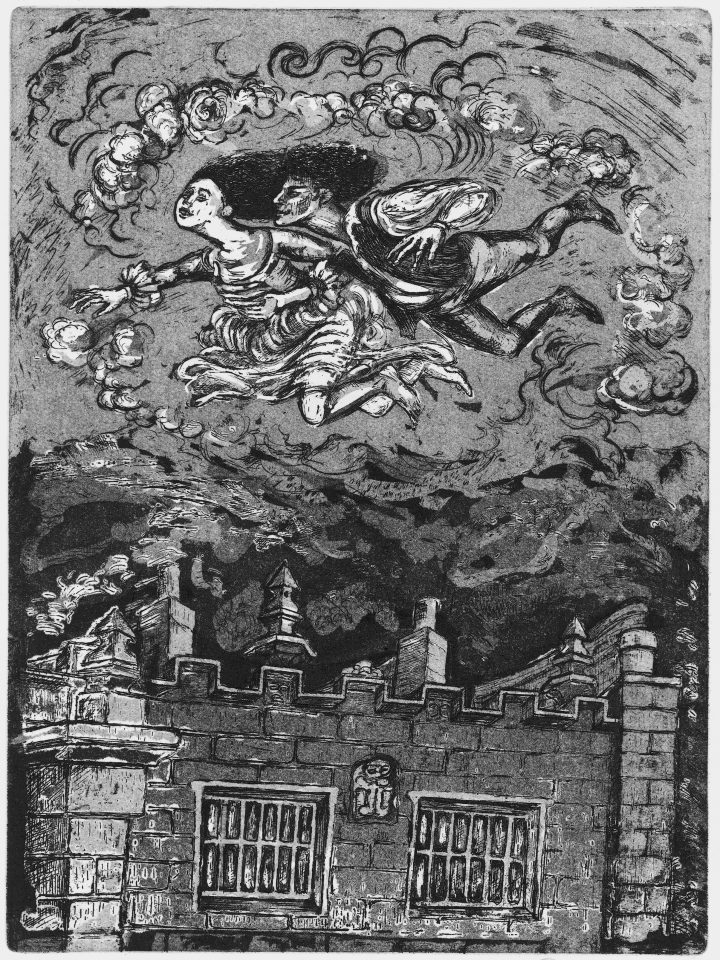

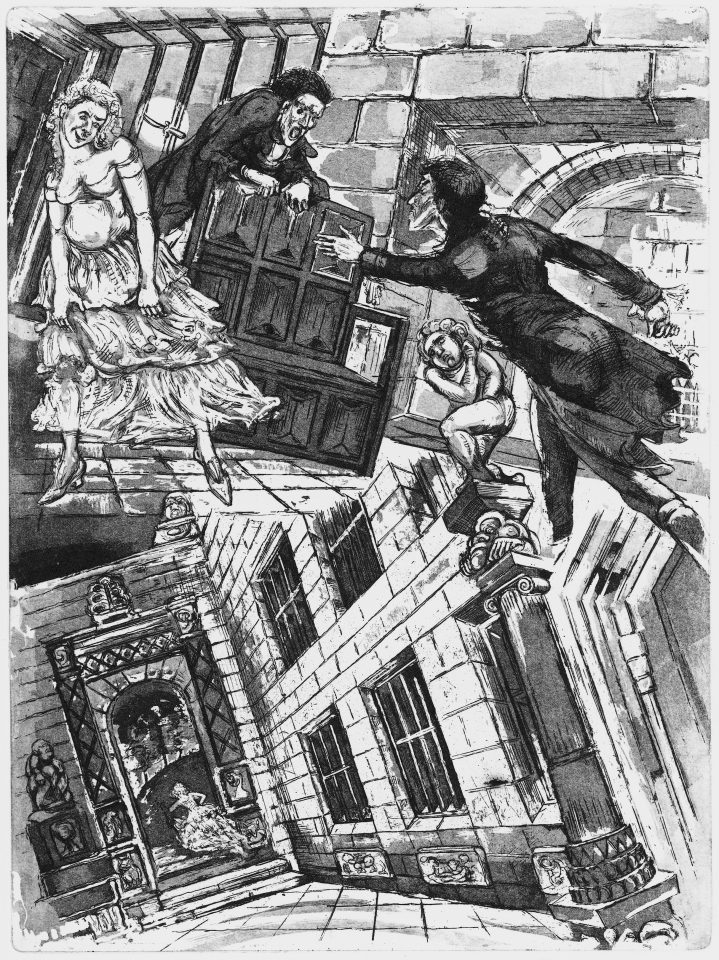

Flight Over Rooftops, etching

-

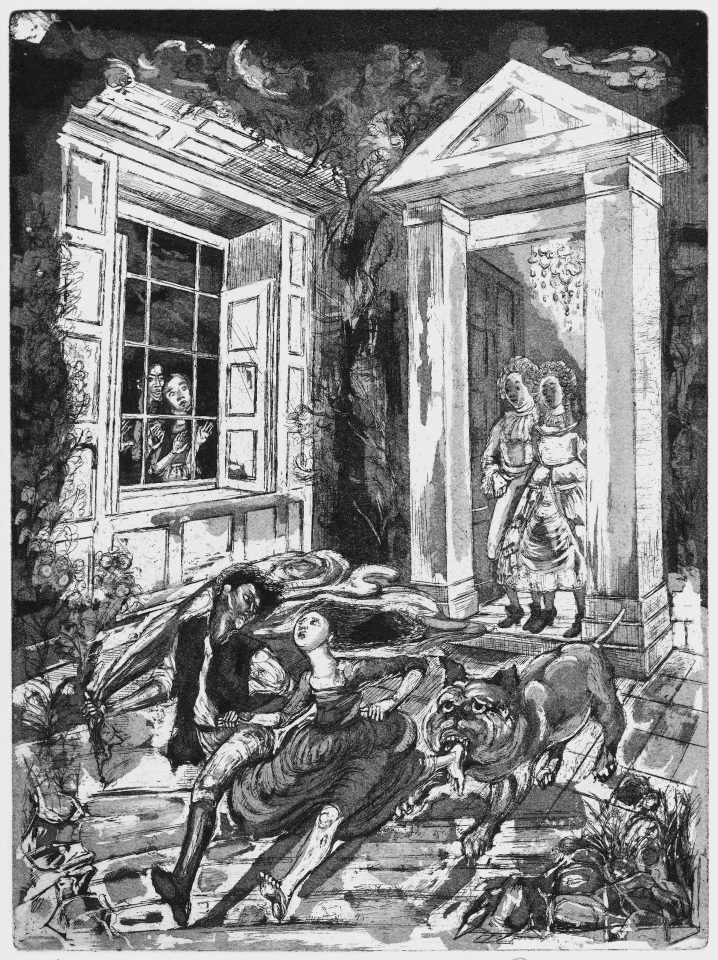

Bulldog Bite, etching

-

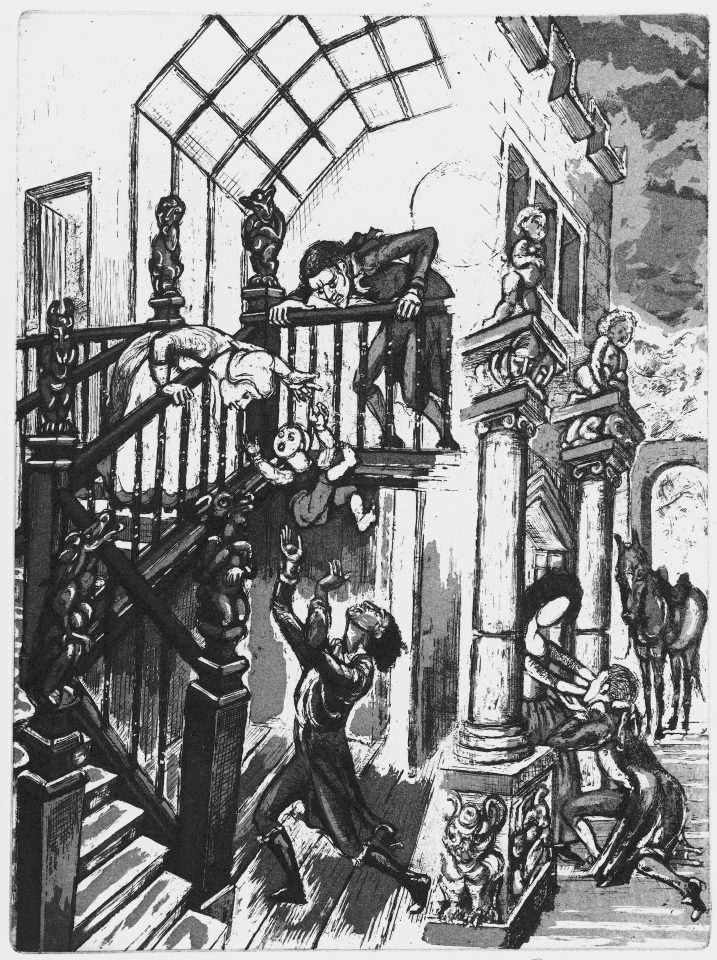

The Fall of Hareton, etching

-

Storm over the Heights, etching

-

The Return of Heathcliff, etching

-

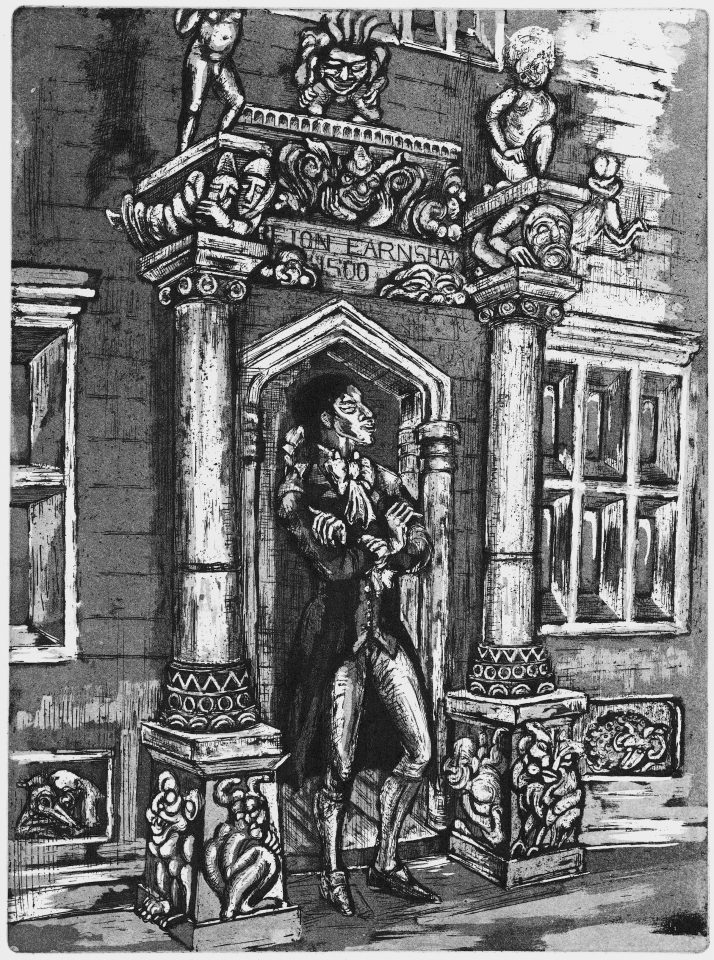

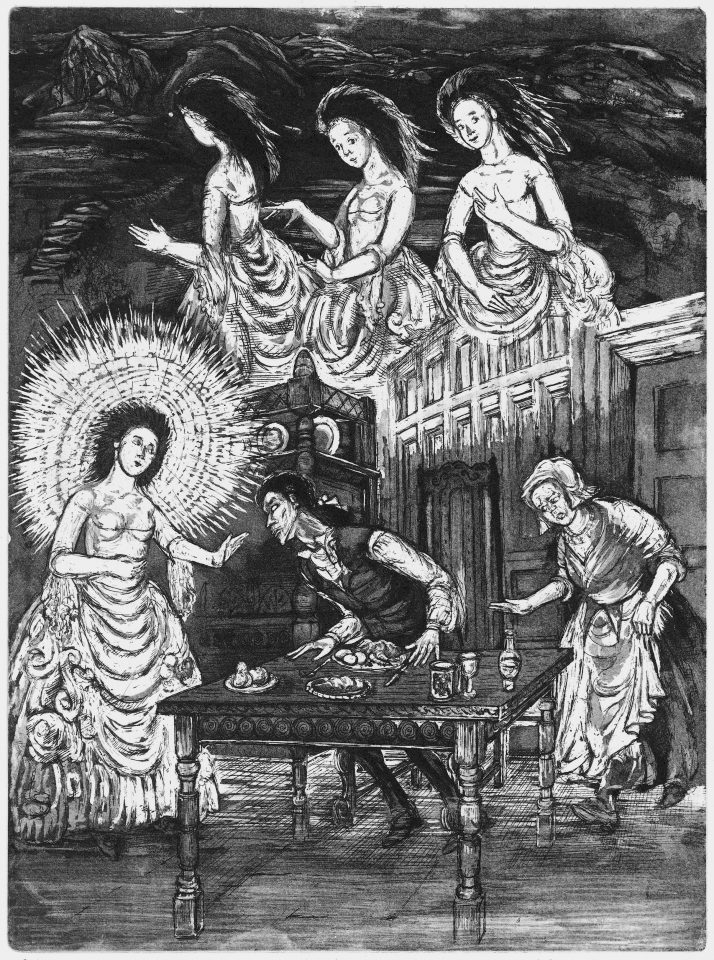

A Perfect Misanthropist’s Heaven, etching

-

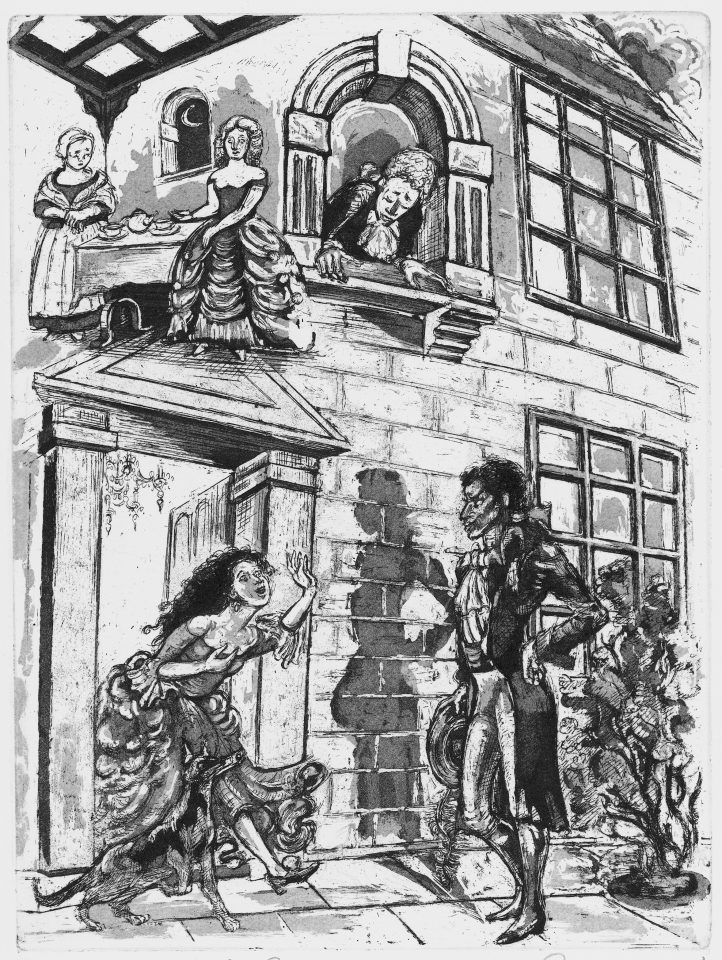

Heathcliff Embraces Isabella, etching

-

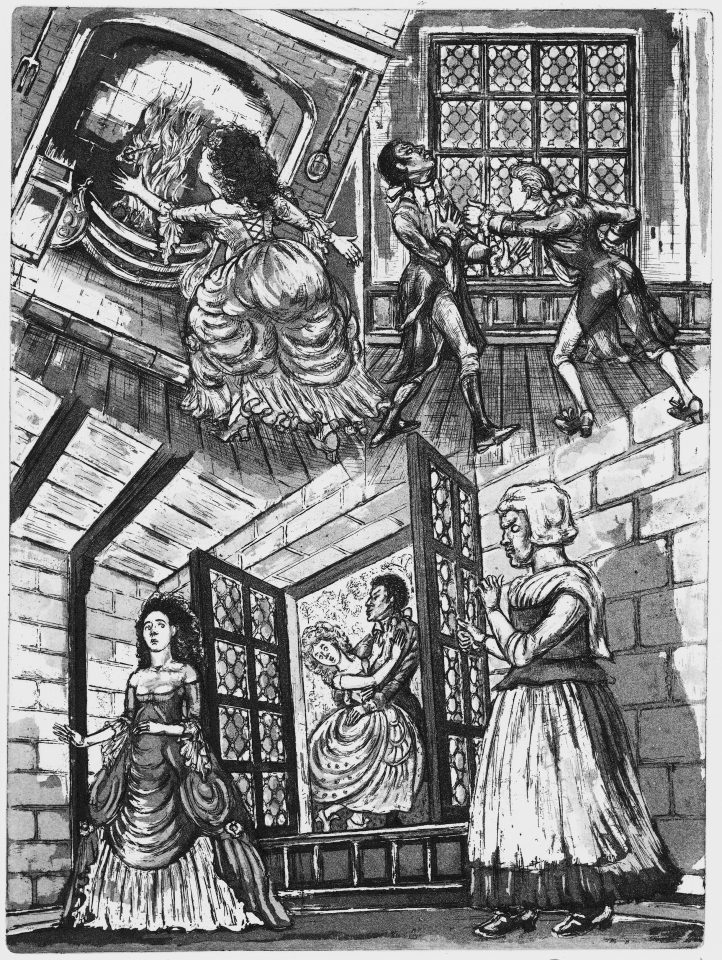

Deranged at the Grange, etching

-

The Last Meeting, etching

-

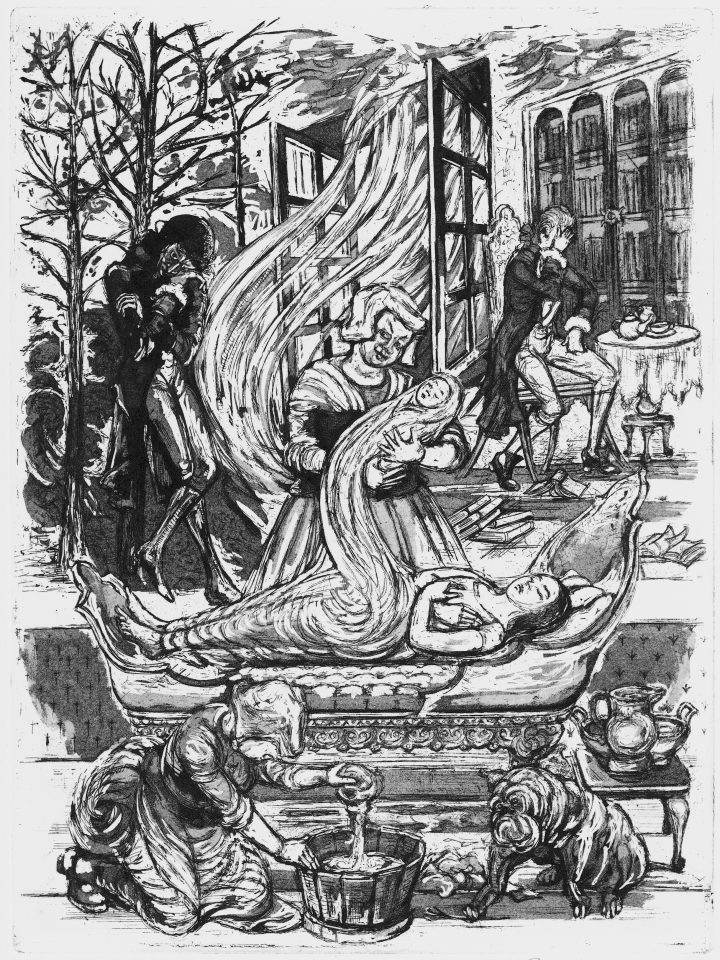

Birth and Death, etching

-

Isabella Escapes Her Tormentor, etching

-

Absorbing Subject, etching

-

Transfiguration, etching

-

The Death of Heathcliff, etching

In works inspired by the text of Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, I discovered many parallels with my own artistic concerns - in the formal devices and thematic aspects of content which are important elements contributing to imagery, and in the composition and structural motifs. Brontë’s writing reveals the following preoccupations: interior/exterior worlds explored symbolically (as in indoors versus outdoors); exploration of different conceptualisations of Paradise or Heaven and a profound sense of loss; Heaven and Hell exemplifying oppositional forces and, in the character of Heathcliff, the Mercurial archetype (reminiscent also of Lucifer in Milton’s Paradise Lost).

Brontë juxtaposes opposing forces throughout her narrative such as nature versus culture and order versus disorder, for example in the contrasts she draws between the refined domesticity of Thrushcross Grange and the wild disorder of Wuthering Heights. Catherine yearns to return to the expansiveness of the moorlands and the familiarity of Wuthering Heights, the house of her childhood, but grows steadily more ill, confined inside the seemingly claustrophobic, domesticated luxury of Thrushcross Grange, her marital home. There is also the juxtaposition of need versus want: Catherine needs Heathcliff, while wanting Linton. Brontë’s question, it seems, is how these opposing, dynamic forces may or may not be resolved. ‘Opposition is true friendship’, writes Blake, and I find in Brontë’s writing also, the alchemical concept or proposal of a “union of opposites”.

As Brontë’s tale progresses, all is subject to an unending process of transformation. In the pathetic soliloquy uttered at the approach of her death Catherine, having failed to recognise her own reflection in a mirror, demands of Nelly, ‘Why am I so changed?’ Characters die; new ones are born; others, again, die, yet the same story continues to unfold, albeit with differing emphases and viewpoints. This unceasing sense of unfolding to me, encompasses an alchemical conceptualisation of process and transformation. Brontë’s writing demonstrates a constantly experienced awareness of dichotomy and implicitly suggests a resolution, in dissolution, as for example when Heathcliff plans to be buried as close to Catherine as he can, their bodies mutually dissolving into the earth.

Catherine remarks, 'I’ve dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas; they’ve gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the colour of my mind.’

This description of dreams and dreaming, of living and imagining, in my mind seems to epitomise a mysterious trans-substantial sense of “being worked upon”.